Guest Post: David Ayres, Minister of the Word, Bammel Church, Houston, TX

Our youngest son will be celebrating his 6th birthday this week and, if I had gotten my way, he would have been born a day earlier than he was. Six years ago, when we were scheduling my wife’s c-section, we were given two options – he could be born either on March 1st or on March 2nd. It just so happened that Ash Wednesday fell on March 1st that year and I was immediately drawn to the idea of our son being born on that day. I loved the poetic irony of welcoming a new life into the world on the very same day we are told, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” My wife, however, protested. In horror, she envisioned our first pictures with our new baby marred by a large, dark glob on my forehead. So, I conceded, and our son was born on March 2nd, a day that also happens to be a sacred holiday where I am from: Texas Independence day.

While I have no regrets with our decision, I still appreciate the rich symbolism of celebrating a birth on Ash Wednesday. Because, in a certain sense, we are all born on Ash Wednesday. We are all born into death. The moment we are born, death becomes an inescapable part of our destiny. From day one, we are dust and to dust we will return.

Wilderness

Dying is part of what it means to be human. Which is precisely why we are so anxious to avoid being human. We have ingenious ways of avoiding our humanity. Either by losing ourselves in our most basic, animal instincts – a life confined to the pursuit of food, sex, and comfort. Or we try to sublimate our humanity by becoming more than human – too rich, too famous, too powerful to see how frail we actually are. Either way, we are desperate to be anything but human.

Which is why the gospel reading for the first Sunday of Lent always focuses on the story of Jesus’ testing in the wilderness (see: Matt. 4:1-11). If you know the story, you remember that Satan comes to Jesus with three temptations. In the first, Satan tells Jesus, who had been fasting for weeks at this point, to satisfy his hunger by turning a stone into bread. In the next temptation, Satan tells Jesus to jump off the pinnacle of the temple, suggesting that his identity as the Son of God would make him invincible from injury. Finally, Satan shows Jesus all the kingdoms of the world and offers to give Jesus authority over all of them, if he would just bow down and worship Satan.

Can you see what Satan is up to here? Satan trying to get Jesus to re-define what it means to be the Son of God. And it has everything to do with Jesus denying his humanity. Because here is what Satan wants Jesus to believe being the Son of God means: I'll never have to be hungry. I'll never get hurt. And no one will have authority over me.

Simply put, Satan is trying to get Jesus to give up being human. Satan wants Jesus to be more God than human.

Because God doesn’t get hungry. But we do.

God can’t be injured. But we can.

God is all-powerful. But we aren’t.

Can we just pause and acknowledge how tempting these temptations actually are? If you could guarantee your own safety and the safety of those you love, wouldn’t you do it? If you could make sure you never went hungry and that God never let anything bad happen to you and no one more powerful than you could ever take advantage of you, wouldn’t you take that deal?

That is what Jesus was being tempted with. As the Son of God, he didn’t have to be vulnerable to this broken world like we do. He could have made himself exempt from all of the pain and tragedy that befalls us. But at every turn, Jesus says, “No!” He refused to exempt himself from how painful and scary it is to be human. Jesus did the very thing we are all so desperate to avoid; he remained human.

And from that moment on, the cross was inevitable. What gets revealed in the desert is that Jesus will refuse to abandon his humanity – even if it costs him his life. He would be just like us. Willing to be dust, and to return to the dust.

And that is why Lent insists on confronting us with the inevitability of our demise. Not to instill despair, or to give us time to wallow, or to terrify us into better behavior. When Lent shows us our deaths, it is grabbing our face and setting our eyes in the direction of our salvation.

Ashes to Ashes

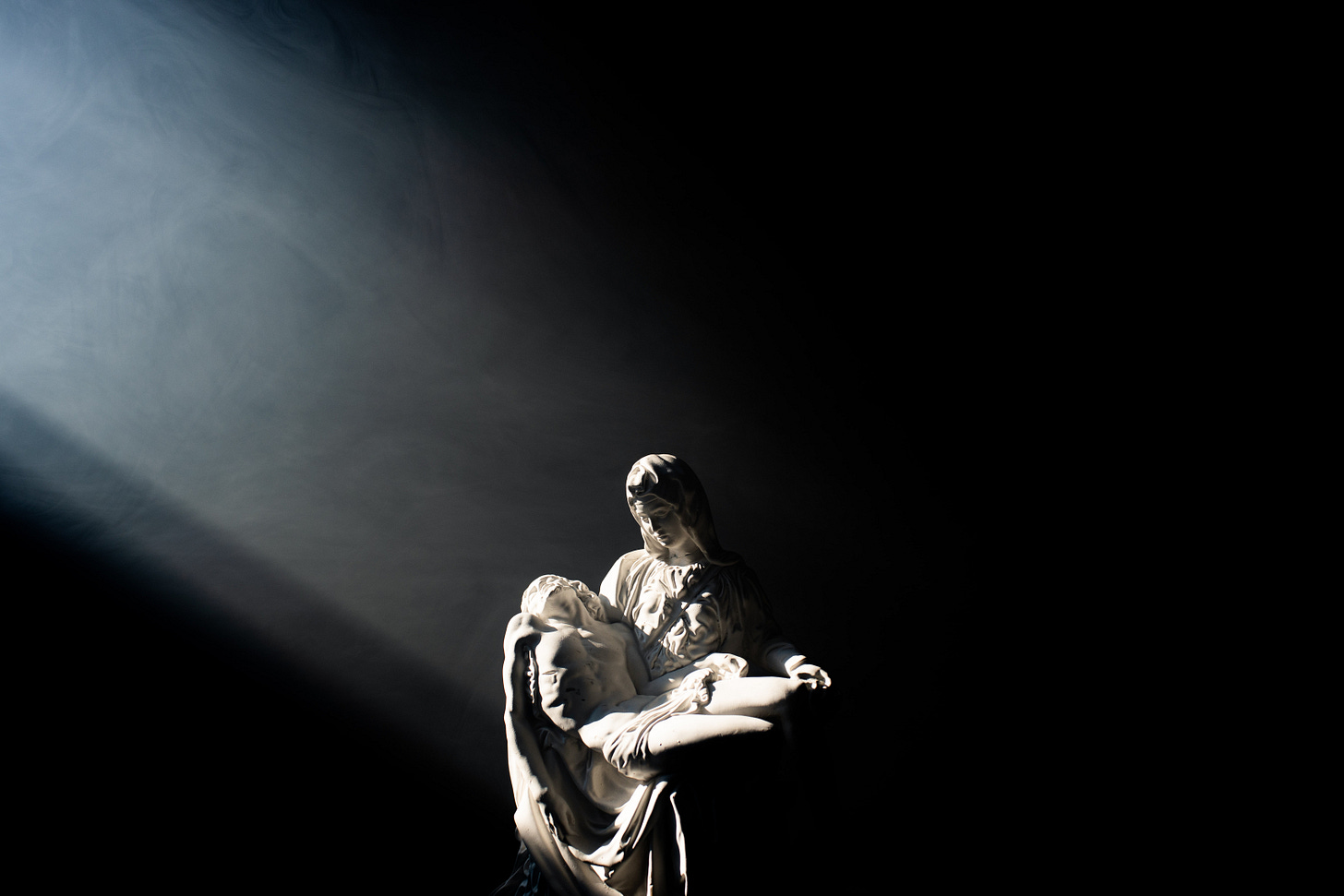

In our fragile humanity, we are desperate for a god who can save us from ever experiencing death. And not just literal, physical death – all the smaller deaths we experience, as well - illness, poverty, rejection, loss. But God doesn’t save us from death, he saves us through death. In and through Christ, God performs a greater miracle than death prevention. God obliterates death all together. God doesn’t just delay our deaths, God is victorious over our deaths.

And we know that, because that’s exactly what happened to Jesus. As theologian, Chris E.W. Green, is fond of saying: God didn’t keep Jesus from dying, he delivered him from death. And God will do the same for us.

That’s what the crosses on our foreheads are meant to remind us. Yes, we are dust. We will not be kept from dying. But our deaths can be like the death of our Christ, the Son of God, the risen one. And in this hope, just as Jesus chose to remain human, so can we.