My journal app asked, “What happened today?” I typed, “My brother died.” And that was the beginning and end of last Friday’s entry.

I’ve always been terrible at journaling, but for the last 30 years I’ve tried. I’ve given it my best shot this year since I’ve been off social media (mostly) and thought I would capture my thoughts as the year progressed. Even with that, I’m not that good about writing a journal. But Friday was different. My journal asked a question, as it does every day. I responded with the shortest entry of my life. Yet, that short entry captured multitudes. My big brother, Richard Earl Palmer, Jr. died unexpectedly in the early morning of July 21, 2023.

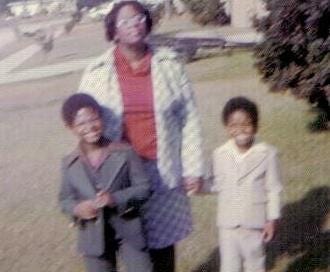

Richard and I were brothers, which is to say, like many brothers, we spent our childhood testing and fighting with one another. Only in the last decade, as we lived in different cities and perused different paths, did we realize how similar we were — particularly our love of wine, bourbon, and sharing wine and bourbon with friends. We both found great delight and meaning in serving the local church. Like most siblings, our common upbringing meant we cherished many of the same things and presented a vast array of others things we didn’t understand about one another.

People keep asking, “How are you doing?” And, most of the time, I have few words to answer that question.

There is no English word for when someone loses a sibling. If there were a word, I’d say it was “lonely,” at least for those of us who grew up with just one sibling. As the youngest, when my parents weren’t around, Richard was. An older brother is your first friend and your first enemy. You’re blood brothers from the start and even when apart there is DNA, memories, and a host of other traits that make you undeniably brothers. I walked around his house seeing so many things I do. I do them differently, but they are, in their essence the same. The love of music, bourbon, wine. In a strange way, a brother’s life, his choices, dreams, and outcomes are like a multiverse of your own. Different decisions. Different outcomes. Same impulses. Same backstory. Same hopes to overcome whatever those formative years delivered to your shared doorstep. So many of the same joys, the same pains, the same trips, the same disappointments, the same untangling of your parents’ journey as you walk your own. Brothers are a different kind of same.

That’s the loneliness, I guess. An alternative version of me no longer lives. There is another mind, another heart, in so many ways dissimilar from me and in so many ways the same, that has stopped beating, making my heart beat at a frequency where there was, but no longer is, a receiver who can understand.

In so many ways, all I’ve ever wanted out of life is to be understood. Richard did.